A talk by Terry Sackett

Terry Sackett gave the February Evening Talk in the Library, taking us on a journey through the changing faces of landscape and country life as seen through paintings. Quite extraordinarily, there was almost no interest in landscape painting and the realities of country life in England until the middle of the 18th century. Yet just across the Channel, in Holland, landscape painting was hugely popular. Terry began with this because it had a lasting effect on the painting of the countryside and rural life in Britain.

Jacob van Ruisdael was the foremost landscape painter of the day and slightly younger than Meindert Hobbema. We viewed paintings by them both, including Hobbema’s ‘A Wooded Landscape’. He had a significant influence on the development of landscape painting in England. Gainsborough was influenced, and Sir George Beaumont, a close friend of Coleridge and Wordsworth, often kept a Hobbema engraving at his side while he painted. A generation before them, the Antwerp master Peter Paul Rubens painted glorious landscapes in addition to his better-known portraits. Constable found in ‘ Landscape with a Rainbow’ a ‘dewy freshness with the departing shower and exhilaration of the returning sun’. Like van Ruisdael, Rubens loved painting stormy skies and bursts of sunshine in rich colours.

Landscape painter and garden designer Coplestone Warre Bampfylde was born at Hestercombe in 1720. He went on the Grand Tour, and the idealised landscapes of Claude and Poussin influenced his paintings. There is no finer example of the effect of the Grand Tour on British landscapes than Henry Hoare II’s Stourhead, with its temples and grotto all carefully positioned around a lake. The buildings are all sited to provide surprise glimpses and vistas for visitors circling the park, so it is a composed landscape, just as a painting is, using contrasts of light and shade.

The Hestercombe landscape garden was created between 1750 and 1791. It includes pools, cascades, summer houses, temples, seats, and urns, all carefully arranged in the best classical tradition. If you walk up to the highest Gothic temple, you will see how the landscape ‘borrows’ the surrounding countryside, enlarging the prospect.

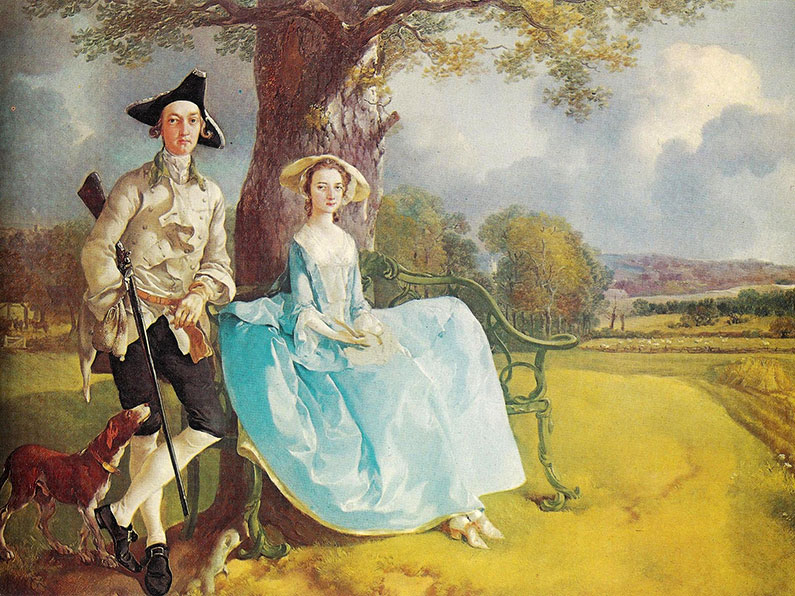

Richard Wilson and George Lambert borrowed from Claude, although Lambert’s ‘A View of Box Hill’ could be the first English landscape painted for its own sake. Despite his reputation as a portraitist, Thomas Gainsborough failed to generate a severe interest in English landscape painting among the British public. George Morland’s best compositions focus on the unembellished lives of country people. The 18th century was the Age of Reason. Everything, including Nature, was ultimately under the control of man. In 1757, Edmund Burke published ‘A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. When we contemplate the Sublime in the form of a mountain or a raging river, our faculty of reason is overwhelmed. The Sublime generates our strongest passions, often grounded in feelings of threat and terror.

In 1793, we found ourselves at war with France. The Grand Tour through Europe was no longer possible, and artists had to look for suitable subjects closer to home. If we didn’t have the classical ruins of Rome in Surrey or Suffolk, we did have a wealth of medieval ruins, including churches, abbeys and castles. Tintern Abbey was a favourite subject, painted by Turner, amongst others.

A movement grew, seeking to harmonise elements of the Sublime with what was Beautiful in landscape forms. In his ‘Three Essays, ’ William Gilpin created a set of rules for assessing landscapes in a new philosophy that became the Picturesque. He said, ‘I am so attached to my picturesque rules that if nature gets wrong, I cannot help putting her right’!

Visitors flocked to Britain’s beauty spots, particularly the Lake District with its rocky fells, all rich in elements of the Sublime. The new tourists were keen to buy prints showing the places they visited. Artists had prints made of their sketches that sold in the hundreds. It was the world of the ‘topographer’. In Terry’s novel ‘Cut and Run’ a typical artist shares his experiences of the topographer’s lot. Thomas Girtin was among the most influential of the new professional topographical artists. His early death at 27 caused Turner to remark ‘Had Tom lived I should have starved.

Turner began as a topographical illustrator, pursuing ruins and mountainous country on horseback, which are associated with the Picturesque and Sublime.

The most important movement of British watercolour artists was the Norwich School, characterized by Cotman and Cox. Cotman’s ‘Greta bridge’, built up in distinct tonal planes of restrained colour, still looks incredibly modern. In Cox’s ‘A Windy Day,’ he works with a boldness and freedom of expression comparable to late Impressionism. He rejected the fine detail characteristic of Constable, concentrating on the overall effect.

Constable returned time and again to the flat Suffolk country of his boyhood. His profound understanding of it grounded his deep love of the Stour Valley as a working landscape. He said, ‘It would be difficult to name a class of Landscape in which the sky is not the keynote. The sky is a source of light in Nature – and governs everything. Unlike Constable, Samuel Palmer was less interested in the fundamental nature of country life, and his fields and woods conjured a mystical calm.

Terry continued his talk with illustrations of the work of John Ruskin and members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The Victorian age saw a considerable growth in literacy and the spread of illustrated books and magazines. The illustrations were drawn by highly gifted artist-craftsmen and engraved on steel blocks. Deadlines were tight, and they had to work fast, yet the overall quality of their work was outstanding. Their engravings were often used to reproduce the paintings of major artists. Now everyone could afford prints of their work.

George Clausen’s paintings fittingly ended the talk. Clausen shows farm labourers in wet and muddy fields, wrapped up against the wind, hoeing, lifting and cutting turnips. The paintings are unsentimental and a far cry from the fake rusticity of some earlier painters.

Thanks to Terry for loaning the 24 pages of his ‘script’, which he wrote to accompany his talk and which is largely used to create this report.